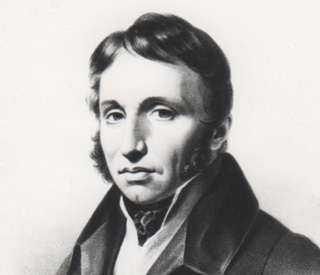

| Paul-Louis Courier Courrierist, lampooner, polemist |

|

Insensé qui croit asservir et se dispenser d'obéir…

M'est avis que cet enchaînement de sottises et d'atrocités qu'on appelle histoire ne mérite guère l'attention des hommes sensés.

Parler est bien, écrire est mieux ; imprimer est excellente chose. Car si votre pensée est bonne, on en profite ; mauvaise, on la corrige et l'on profite encore.

La noblesse n'est pas de rigueur pour entrer à l'Académie ; l'ignorance, bien prouvée, suffit.

Les gens qui savent le grec sont cinq ou six en Europe ; ceux qui savent le français sont en bien plus petit nombre.

Ce ne serait rien d'avoir tué quinze ou vingt mille hommes, par exemple. Avec cela on est à peine nommé dans l'histoire. Pour y faire quelque figure, il faut massacrer par millions.

Femme qui prête l'oreille prêtera bientôt autre chose.

Rendons aux grands ce qui leur est dû; mais tenons-nous en le plus loin que nous pourrons, et, ne nous approchant jamais d'eux, tâchons qu'ils ne s'approchent point de nous, parce qu'ils peuvent nous faire du mal, et ne nous sauraient faire de bien.

De l'acétate de morphine, un grain dans une cuve se perd, n'est point senti, dans une tasse fait vomir, en une cuillerée tue, et voilà le pamphlet.

L'apostrophe, c'est la mitraille de l'éloquence.

Je n'ai fait pour être des vôtres que quarante visites seulement, et quatre-vingts révérences, à raison de deux par visite. Ce n'est rien pour un aspirant aux emplois académiques ; mais c'est beaucoup pour moi, naturellement peu souple et neuf à cet exercice.

On écrit aujourd'hui assez ordinairement sur les choses qu'on entend le moins. Il n'y a si petit écolier qui ne s'érige en docteur. A voir ce qui s'imprime tous les jours, on dirait que chacun se croit obligé de faire preuve d'ignorance.

Mieux vaut tuer un marquis, disent les médecins, que guérir cent vilains : cela vaut mieux pour le médecin ; pour les ministres non ; mieux vaut tuer les vilains.

Mais une notice d'un livre par quelqu'un qui ne l'a point lu est une bouffonnerie toute neuve

Il faut hurler avec les loups, d'autres disent braire avec les ânes, mais il ne faut pas s'aller fourrer parmi les ânes et les loups.

Elles [Les Calabraises] sont noires dans la plaine, blanches sur les montagnes, putains partout ; Calabraise et braise, c'est tout un.

Qu'on mette un roi à Genève avec un gros budget, chacun quittera l'horlogerie pour la garde-robe.

Il faut hurler avec les loups, d'autres disent braire avec les ânes, mais il ne faut pas s'aller fourrer parmi les ânes et les loups.

La vie est un brelan où celui qui laisse voir son jeu est assuré de perdre.

Il n'est vilain qui, pour se faire un peu décrasser, n'aille du roi à l'usurpateur et de l'usurpateur au roi, ou qui, faute de mieux ne mette au moins un de à son nom.

La postérité ne se doutera jamais combien, dans ce siècle de lumières et de batailles, il y eut de savants qui ne savaient pas lire et de braves qui faisaient dans leurs chausses.

La vie est un brelan où celui qui laisse voir son jeu est assuré de perdre.

Soldat pendant longtemps, aujourd'hui paysan, n'ayant vu que les camps et les champs, comment saurais-je donner aux vices des noms aimables et polis ?

Quelque grands que soient nos péchés, nous n'avons guère maintenant le temps de faire pénitence. Il faut semer et labourer.

Je conteste fort peu : j'aime la liberté par instinct, par nature.

Né d'abord dans le peuple, j'y suis resté par choix. Il n'a tenu qu'à moi d'en sortir comme tant d'autres qui, pensant s'ennoblir, de fait ont dérogé.

Une pensée déduite en termes courts et clairs, avec preuves, documents, exemples, quand on l'imprime, c'est un pamphlet et la meilleure action, courageuse souvent, qu'homme puisse faire au monde.

Oh ! qu'une page pleine dans les livres est rare ! et que peu de gens sont capables d'en écrire dix sans sottises.

La gloire aujourd'hui est très rare : on ne le croirait jamais ; dans ce siècle de lumières et de triomphes, il n'y a pas deux hommes assurés de laisser un nom.

J'aime mieux vous dire en un mot ce qui me distingue, me sépare de tous les partis, et fait de moi un homme rare dans le siècle où nous sommes ; c'est que je ne veux point être roi, et que j'évite soigneusement tout ce qui pourrait me mener là.

Vous êtes bien bon de vous occuper des grands hommes. J'en ai vu depuis deux ou trois : c'étaient de plats personnages.

Si l'on savait ce que c'est, les rois descendraient du trône et personne n'y voudrait monter.

Mais dites-moi, je vous prie, vous qui avez couru, sauriez-vous un pays où il n'y eût ni gendarmes, ni rats de cave, ni maire, ni procureur du roi, ni zèle, ni appointements (…) ni généraux, ni commandants, ni nobles, ni vilains qui pensent noblement ? Si vous savez un tel pays, montrez-le-moi, et me procurez un passeport.

Justice, équité, providence ! vains mots dont on nous abuse ! Quelque part que je tourne les yeux, je ne vois que le crime triomphant, et l'innocence opprimée.

On est quelque chose en raison du mal qu'on peut faire.

Tout vice vient d'oisiveté, tout désordre public vient du manque de travail.

Trop d'aise le rend insolent [le peuple] ; il faut le faire payer pour lui ôter ce trop d'aise. Trop peu l'empêche de payer ; il faut lui laisser quelque chose comme aux abeilles on laisse du miel et de la cire.

Chacun se lance ; non : à la cour, on se glisse, on s'insinue, on se pousse.

Je suis Tourangeau, j'habite Luynes…

La Charte vint, on me dit : Parlez, vous êtes libre, écrivez, imprimez (…) Moi pauvre, qui ne connaissais pas le gouvernement provocateur, pensant que c'était tout de bon, j'ouvre la bouche et (…) on me met en prison.

Dès l'âge où j'ai commencé à faire quelque usage de mon intelligence, j'ai eu le désir de m'instruire, et la passion de l'étude.

La vérité, dites-vous, ne veut aucun ornement ; tout ce qui la pare, la cache. Peignez-la donc nue mais belle ; qu'elle frappe et plaise en même temps.

Né d'abord dans le peuple, j'y suis resté par choix.

La douleur raisonne peu. Comme elle ébranle au contraire la raison la plus ferme et trompe le sens le plus droit !

La prairie une fois fauchée, que fait à telle ou telle fleur d'être tombée le soir ou le matin ?

L'éloquence vit de passions, et quelles passions voulez-vous qu'il y ait chez un peuple de courtisans, dont la devise est nécessairement : Sans humeur et sans honneur.

J'ai eu à me plaindre des grands, des femmes, de mes amis et de moi-même. J'ai pardonné à tout le monde, et gardant toujours la même indulgence, je m'abandonne à la fortune, content qu'elle ne me mette jamais ni trop haut ni trop bas.

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||

France

France Suisse

Suisse aul-Louis Courier, with such a typically French mind was on familiar terms with Ancient Greece and proved the poets wrong. At least one of them: Le Tasse. If one does not question his Delivered Jerusalem the Touraine province would be gentle, pleasant and delightful and its inhabitants in harmony with it. This picture is unquestioned by a native of Touraine, Balzac, that fine connoisseur of the Garden of France.

aul-Louis Courier, with such a typically French mind was on familiar terms with Ancient Greece and proved the poets wrong. At least one of them: Le Tasse. If one does not question his Delivered Jerusalem the Touraine province would be gentle, pleasant and delightful and its inhabitants in harmony with it. This picture is unquestioned by a native of Touraine, Balzac, that fine connoisseur of the Garden of France.